Four types of creativity

There are many different ways of being creative.

In college, I had a few friends who liked to freestyle. Not in a serious way, but just for fun at random moments. We even had a little structure we’d use walking home from a party or bar on frigid Montréal nights where we’d each improvise a song on the fly, but it had to end with the lyric “everybody’s working for the man.”

I can’t say I was particularly successful at this game.

Whereas others would introduce a verbal slight of hand here or a miraculously smooth landing there, I’d often be stuck in a little tourbillion of clichés and lameness. Though, to be honest, I was pretty happy I managed anything at all, since I’ve never considered thinking on my feet a great strength of mine.

And yet, despite not being a great freestyler, I feel myself to be a very creative person. I make a lot of stuff — art, music, projects, coloring books, giant snake heads for candy chutes on Halloween. I once made a mural on my kid’s bedroom wall of an underwater / outer space scene that involved a giant squid wrestling with a spaceship. I improvise on the piano every single day.

Creativity is often presented as a single thing. Some people are thought to be “more creative” than others. As a kid, people used to say you were either “left-brained” and analytical or “right-brained” and creative. It would be easy in some ways to see my freestyling buddies as more creative and me as less so, and even to internalize that.

But that seems so obviously untrue, even if this type of thinking occasionally creeps in. Creativity just has different forms it can take.

This week, I stumbled across the writings of neuroscientist Arne Dietrich, who studies the neuroscience of creativity. I’m a fan. Here’s one of his quotes:

“We might think of creativity as a cohesive entity in psychological terms, a character trait that some people have more than others – notice the singular – but creativity, as such, might not exist as a distinct and separate entity in the brain.” — Arne Dietrich, Types of Creativity

Basically, Dietrich argues that we don’t have a clear, unified understanding of how creativity works in the brain, in part because creativity is vastly more complex and multifaceted than we’ve recognized up til now.

For example, researchers often used to rely on the ability to generate unexpected ideas from scratch — divergent thinking — as a way to measure creativity, but Dietrich and others pointed out that’s just one form of creativity. What about iterating? What about ideas drawn from synthesis and reflection? What about using rules and constraints to generate ideas? All of that stuff can be very creative. I don’t feel like I’m being particularly “divergent” right now, but isn’t writing this a creative act of sorts?

In other words, we’re complex beasts, and creativity is a big part of why. It’s not something that’s easily pinned down and measured — like looking at a herd of intermingled zebras with criss-crossing arrays of fervent stripes vibrating out in different directions and trying to determine where the actual zebras are.

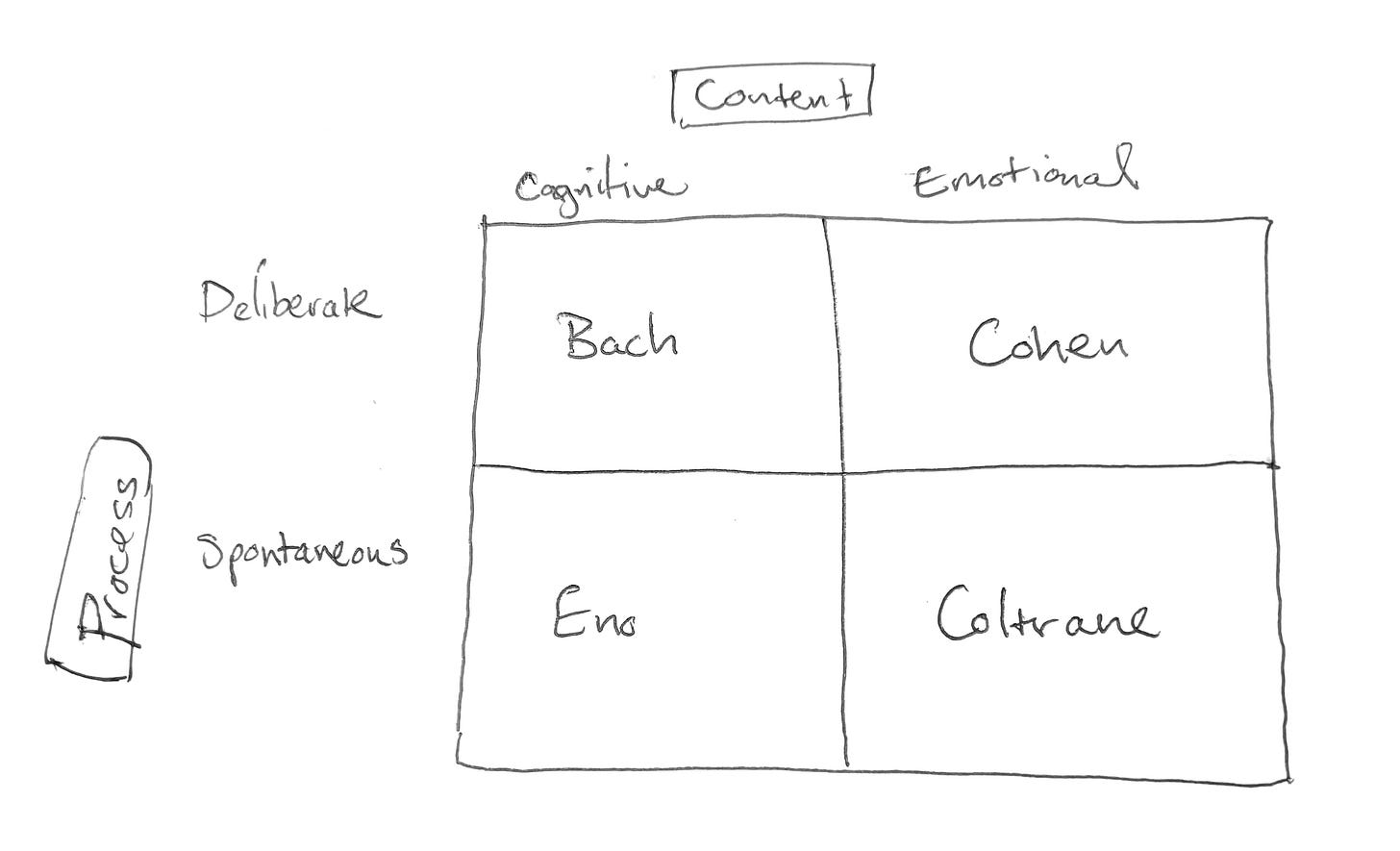

There was one part of Dietrich’s writing I particularly locked onto. In 2004, he came up with this cute little 2:2 matrix for different “subtypes” of creativity. The matrix is formed by crossing these two axes:

Deliberate vs Spontaneous. Are ideas the result of conscious planning or do they bubble up unexpectedly?

Cognitive vs Emotional. Are we drawing on analytical skills and knowledge or emotions and feelings?

To be clear: These are not personality types. These are different types of creativity we can all access, though maybe some come more naturally to you than others.

To help myself understand this matrix and how it can be useful, I came up with some archetypes for each quadrant — artists whose creative process might seem to conform to that approach. To be clear, this is an oversimplification. I am certainly not suggesting these specific artists ONLY used this type of creativity. But maybe they’re useful associations to help illustrate how there are different types of creativity and you can access them at different times and in different ways.

Quadrant 1: Bach

The first quadrant of Dietrich’s matrix is deliberate cognitive. This is prime nerd territory. When you’re creative in this way, you’re engaging in an intentional, conscious process of creativity, drawing on analytical and knowledge-based information to do so.

The first person that jumps to mind is the poster-child paragon of rules-based composing, J.S. Bach. Bach’s pieces have become stand-ins for well-defined structures and clear principles, so much so that his work forms the backbone of many music theory textbooks used today. A Bach invention or fugue can feel like a problem-solving exercise, where a brave little motif is run through a logical and varied compendium of treatments to attain its full expression. The voices in a Bach chorale reliably approach resolution from the right direction.

To be clear, Bach’s music can also be very emotionally powerful, but it’s clear he loved an abstract system and a set of dictates he could master. The Art of the Fugue is one of the best examples. It’s essentially an intellectual exercise, an exploration of how many contrapuntal treatments one can write using a single motif.

So this type of creativity calls for thought, planning, and analysis, knowledge and study. It makes me think of Max Martin and his concept of “melodic math,” where specific lyrical lines need to have specific syllabic patterns to them, or writing a Shakespearean sonnet, where the rules are part of the point.

I often turn on Bach mode when I’ve got a highly constrained project (like composing for a quartet) or when I’m doing something that engages a skillset I’m still learning. I might be flipping between YouTube videos or tutorials and using lots of iterations to apply different techniques.

Quadrant 2: Leonard Cohen

Next up, there’s the deliberate emotional approach, and for this one, I chose the poet, novelist, and songwriter Leonard Cohen.

Leonard Cohen did not compose with any of the rules-based meticulousness of Bach, but he was highly process-oriented and deliberate in his approach. Cohen believed deeply in coming up with many different drafts and iterating on them relentlessly, so much so that he never considered any of his songs finished, calling them all simply “versions.” For him, the songwriting process was a series of deliberate steps taken to uncover a specific song. “It takes me a great deal of time to find out what the song is,” he once said,

“Before I can discard the verse, I have to write it… I can’t discard a verse before it is written because it is the writing of the verse that produces whatever delights or interests or facets that are going to catch the light.” — Leonard Cohen, Songwriters on Songwriting

At the same time, Cohen is fundamentally a poet. His interest is not in applying some specific rule to his writing, but in uncovering deep wells of feeling and emotion he believes are hidden behind his more “bureaucratic” everyday thoughts. His iterative process is in fact one of digging deep into his psyche to unearth what’s there that’s meaningful.

So this type of creativity is about process and reflection. It’s less about applying a specific skillset or rulebook, and more about drawing out your thoughts, feelings, and emotions. You’re accessing this type of creativity when you journal or put aside time for reflection or edit something with an eye to its emotional resonance.

I’ll admit I don’t usually start with Cohen mode personally — I tend to use this in editing more, when I’ve got some idea already and am trying to make it say what I want it to say. I’m using my emotional insights and responses to shape an idea.

Quadrant 3: Brian Eno

The bottom left quadrant is the spontaneous cognitive. This is where you’re creating the conditions for ideas to bubble up unexpectedly, but drawing on a specific set of knowledge or skills.

For this one, my mind jumped to Brian Eno and his focus on engineering systems to produce an unexpected outcome. The spontaneous aspect is obvious — he even talks about “not interfering” with his music, except insofar as he chooses which experiments work and which don’t. That’s a huge contrast to Bach and Cohen.

And yet, his approach is also cognitive in that it’s highly intellectual at times. He’s coming up with specific processes and systems to generate a cognitive response that can guide the way forward.

His Oblique Strategies cards are a great example. They’re a series of prompts designed in partnership with Peter Schmidt that range from the concrete (e.g. “convert a melodic element into a rhythmic element”) to the esoteric (e.g. “give way to your worst impulse”). The aim is to get you out of your familiar patterns and see problems through new lenses, and thus spark new ideas.

So this type of creativity is all about getting out of your own way. It’s intellectual in that you’re being very intentional about your process, but in order to allow unexpected ideas and surprise to surface. This is probably the type that my freestyling buddies were using.

I find Eno mode endlessly useful, especially for generating new ideas. What can I do with 3 notes and an odd time signature? What happens if I write a song with my left hand instead of my right? Shaking up the system in order to access some new thinking is a great way to kick start a project.

Quadrant 4: John Coltrane

Finally, we’re at the spontaneous emotional quadrant. This is where you’re opening the door for unexpected ideas from an emotional rather than intellectual core.

To me, when I saw this, I immediately thought about live improvised performance and pouring your heart out on stage. Little is planned. Judgment recedes. You’re channeling pure emotion into your work.

And maybe no one embodies that concept more clearly for me than late John Coltrane, when he starts eschewing complex chord changes and searching for freedom and spiritual release in his music. Obviously, Coltrane was an absolute master with a huge range of technique and knowledge to draw on — but his overarching concern at this point seemed to be less about using that knowledge than forgetting it. His songs started to become much longer, more freer, wandering improvisations that border on ecstatic.

So this type of creativity is about channeling your feelings into your music without judgment or planning. It’s often easier if you have a large well of knowledge and skill you can use to communicate that emotion so deeply embedded you don’t need to consciously think about it.

Dietrich also updated his framework a little bit in 2018, adding Flow Mode to the deliberate-spontaneous axis. It feels to me like the spontaneous-emotional quadrant spills out into this Flow Mode area, although the distinction is more about execution than idea generation. In Flow Mode, you’re in a kind of sublime, unconscious moment of execution, but you’re likely drawing on ideas generated from the spontaneous-emotional mode. But also I’m not a cognitive neuroscientist, so what do I know.

I find I can access Coltrane mode in a couple ways, but it’s often fleeting. If I’m on my own at the piano with no expectations, I can sometimes play in a deeply emotional way, especially late at night. Or sometimes I’m able to find it in collaboration when I’m experiencing a deep connection with someone I’m working with. It can be really powerful to record those moments so you can draw on them for future ideas — or just let them exist untouched, uncommented upon, a magic, fleeting moment of beauty, and leave it at that.

The Upshot

So what’s the point of all this?

For one thing, it’s useful to remember that creativity is not just one thing, and there are many ways to be creative. You can walk to the post office, and you can walk to the post office creatively — backwards with your gloves on your ears while whistling a diminished scale and taking multiple unnecessary left turns. Creativity is something you can access in a huge variety of ways, no matter how your brain works.

Additionally, I thought this was a useful framework to think about my creative process on a day-to-day level. You may find reading this list that you resonate with a certain archetype or quadrant more than others, like I do — but you also may find you can tap into these different modes at different times to stretch your creativity to its limits. If you’re in Bach mode all the time but start to feel stuck, maybe it’s time to worry less about the rules and see where your feelings take you. Or if you’re always in Coltrane mode, maybe take a course and try to deliberately employ a new technique through your music to see what that opens up.

So that’s that! I hope this sparks some thoughts about how you can be at your most creative this week — and what sort of systems or approaches you regularly use to be creative.

Oh yeah, and everybody’s working for the man.

And if there are other artists you’d like to put forth as archetypes, pop them into the comments. I’d love to hear about them!

dnekeew taerg a evah,

Ian

Ian Temple

Founder, Soundfly

ian@soundfly.com

Five Interesting Things

If you want to go further with the neuroscience of creativity, I recommend also reading about the interactions between the Executive Control Network and the Default Mode Network, which works nicely with Dietrich’s frameworks as well. Basically, researchers now think creativity is less about regions of the brain and specific networks and the ways they interact.

Someone turned Brian Eno & Peter Schmidt’s Oblique Strategies into a website. It’s not quite the same without the cards, but if you need a little prompt to get yourself unstuck, go here and pick a few prompts.

My friend and journalist Adam Protz has a wonderful interview with the Polish composer Hania Rani about the wide variation of work she’s produced in the past year. It’s inspiring to hear how she approached working with a classical orchestra trying to make it sound more like some of her electronic music: “I wish to all my fellow musicians that they can have this experience of working with a bigger acoustic ensemble, because it is just like working with 45 synthesizers.”

I’m helping run Kiefer’s 30 Days of Improvisation course right now, and it’s a wonderful reminder of the power of transcription — in particular, taking a small phrase you like and applying it to lots of different contexts so you have it for always. I spent the morning using a Mulgrew Miller riff and playing it over about 8 different standards, and it was incredibly fun.

Someone in one of the Discord groups I’m in shared this track “Magnificat” by Erland Cooper, and I can’t get enough of it. Hugely meditative and enjoyable.

Fascinating breakdown of the four different types of creativity! The distinction between them is really insightful.

My first thought on the quadrant - "ehmmmm... I think I'm in a middle." One creative process can draw from all types. Bach might sound the most alien to me, but that's probably because I usually don't know the rules that well on this very explicit level, hah - well, maybe with writing, but even here, I often make spontaneous turns that lead me away from the initial purpose.

What I take from all this is a confirmation that creativity is innate to us. Nobody can say that "they're not creative". A few months ago, I saw a documentary from a guy that interviews artists around the world on the question of creativity. And while it was interesting to see different perspectives, in the end, I was bothered precisely by the fact that he limited the definition of creativity to arts. What about the creativity of people that survive on $1 a day? What about creative problem-solving? What about those who build houses and bridges out of scratch, or re-invent the purpose of tools to meet their own needs? Or are able to imagine social systems based on different rules?

The decisive point, I think, is if (and how) you engage with your creativity. Are you curious about new outcomes? Are you brave enough to make a decision and initiate an experiment, taking on the risk that it might fail? Are you willing to put your time and energy into that?

Our current systems are set on making us believe "normal people" are not creative, precisely because you can't really control people that are conscious about their creativity. It takes you out of tired, helpless consumerism into empowerment of creation. I don't know if Dietrich explicitly talks about creativity outside of "the arts", but I think his framework might be useful to think about it as well.

(... back to my point about writing - I didn't start this comment with an intention of writing a mini-manifesto, haha.)

Let's stay creative.